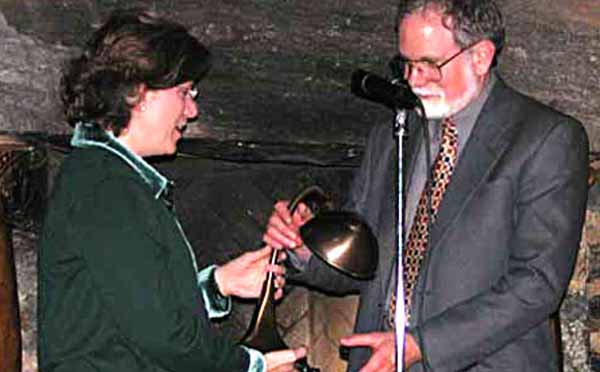

The Association of Legal Writing Directors and the Legal Writing Institute awarded the 2014 Thomas F. Blackwell Memorial Award for Outstanding Achievement in the Field of Legal Writing to Jan Levine at the AALS Conference in New York City.

Jan is an Associate Professor and Director of Legal Research and Writing at Duquesne University School of Law.

As stated in his nomination letter, Jan exemplifies these qualities in several important ways:

For a quarter of a century, he has brought practical strategies for better legal writing education to his students. Through his work as a legal writing director, he has upgraded the legal writing programs at four very different law schools – Virginia, Arkansas-Fayetteville, Temple, and Duquesne – improving directly the legal education of all the students at those schools. In addition, his conference presentations, service, and scholarship have helped an entire generation of legal writing professors innovate and professionalize, helping to improve the legal skills training of many more students across the country. There are scores of legal writing professors and program directors who have benefitted from [his] assistance with their careers and his tireless mentoring, consulting, and strategizing.

Remarks by Jan M. Levine

January 3, 2014

I must thank many friends for this great honor. First, I thank Kathy Vinson, the President of the Association of Legal Writing Directors, and Mel Weresh, the President of the Legal Writing Institute (and David Thomson, who represented LWI here tonight). I also thank the members of the Blackwell Award Committee: Mary Garvey Algero, Lisa Blackwell, Lyn Entrikin, Steve Johansen, Carol Parker, Suzanne Rowe, and Mel Weresh. Of course, I also thank those friends and colleagues who nominated me, particularly my dear friend Sue Liemer, who was unable to come to New York today. I must thank my students and graduate fellows for teaching me so much, especially those who have given me the greatest compliment a teacher can receive, following me into the teaching of legal writing. Finally I thank my wife and son for putting up with me spending so many hours critiquing student papers while at home.

This is a bittersweet day for me, however, because Tom Blackwell was a friend of mine. I remember sitting in a faculty meeting on January 16, 2002, and hearing the news of the shootings at Appalachian School of Law. We then learned that Tom, who was only 41 years old, had been one of the three victims. I met Tom when he was teaching at Chicago-Kent, and I had tried to convince him to apply for an opening we had at Temple. Although I’m supposed to be a pretty persuasive fellow, I was unsuccessful in my efforts because Tom was adamant that he wanted to move his family, Lisa and the children, back to a rural area in the South. I got to know Tom better through work on several ALWD projects; he was our first webmaster and a key member of several committees. Tom was a brilliant, selfless, caring, and committed teacher and colleague. He will never be forgotten by those of us lucky enough to have known him, and when we created this award we wanted to keep his memory alive for others. I hope we have succeeded.

So please join me in the first of two toasts tonight. This first toast is to Tom’s memory and to Lisa and the Blackwell family.

The receipt of this award, the AALS Section award, the start of a new calendar year, and the imminent beginning of a new semester are the kinds of things that causes one to reflect on law school teaching, on one’s career, and the future. So please bear with me for a few minutes as I share some of those thoughts with you, and then ask you to join me in a second toast.

I began teaching legal writing in 1980, two years after I graduated from law school. I taught as an adjunct for two years, and then went into teaching full-time in 1986. Those three decades, most spent as a full-time faculty member and LRW program director at four law schools, have given me a perspective on our field shared by only a few others in our field. The field of legal writing has changed dramatically since I began my career. We have overcome many challenges, but we are now facing reactionary forces that threaten all we have achieved.

When I began teaching, the scholarship about our field was limited to a few textbooks and a handful of articles about legal writing, which one scholar called the “Neglected Orphan of the First Year.”[1] Most of the articles were written about how a law school could teach the course on the cheap, with upper-level students or short-term teachers, because, after all, as another scholar wrote, “[T]here is also no reason to suspect that highly talented and motivated people will long remain in a devalued specialty for which the professional and financial rewards are, respectively, few and small.”[2]

Many schools relied exclusively on adjuncts and upper-level teaching assistants. The predominant staffing pattern for full-time teachers was the short-term contact, which was typically limited, or capped, to a total of two or three years, rarely extending to five. There were fewer legal writing teachers in the nation with tenure than you could count on the fingers of one hand, and most had been tenured for scholarship written well beyond the legal writing area. Starting salaries for legal writing program directors sometimes reached the rarified heights of $30,000 at elite schools. When I went to the biennial Legal Writing Institute conferences in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the turnover in teachers was incredible. Most of the faces were new every time, and many disappeared as quickly as they appeared.

But those who remained have been able to change the field dramatically by persistence, perseverance, and pressure from scholarship and political action. Many of the first and second generation of leaders in our field were children of the 1950s and 1960s, who heeded the Quakers’ call to “speak truth to power.”[3] Many of us have fought a long fight with our deans, our faculties, and the ABA to see our courses become well-accepted, to see the credits allocated to legal writing grow, to see so many colleagues gain tenure and job security, and to see a blossoming of legal writing scholarship that is diverse and wide-ranging. We have seen the academy finally respond to decades of repeated calls from the bench and organized bar for more and better skills training of law students. Our legal writing organizations are strong, our numbers have increased, our salaries are better, our status has become elevated, and our teaching has become more sophisticated and more effective.

Over the past several years, however, we have seen signs of reaction and an accelerating retrenchment that endanger the field of legal writing. Forces and people within legal education have resisted our field’s progress and have tried, in many ways, to co-opt our movement, such as by making us part of the well-behaved establishment. And they have been able to take advantage of other events to divert us from further progress. In 2007 Naomi Klein wrote a book titled The Shock Doctrine[4] that explains how corporations and neo-conservative organizations and individuals have benefitted from actual or perceived crises to force societies to change. This “disaster capitalism” has been defined as “the rapid-fire corporate reengineering of societies still reeling from shock.”[5]

These same principles and some of the same forces outside of legal education have taken advantage of the high cost of legal education, the downturn in the economy, and the education financing bubble to push back on the ABA Standards, to get rid of tenure requirements and job security, and to divert educators and lawyers from paying attention to the critical need for skills training. Worse, these principles have been pushed despite the lowering of educational standards in high schools and colleges, despite the drop in the critical thinking skills of incoming law students, and despite the dearth of training offered to new lawyers by law firms.

In my more cynical moments, I cannot help but observe that so many of the academic critics of tenure and job security failed to voluntarily depart from the ranks of the tenured except when they have the opportunity to secure huge golden parachutes outside of the law school world. And I cannot help but wonder if many of the individuals complicit in these reactionary trends have done so largely to further their own careers as university presidents and provosts, selling themselves to university governing boards as having successfully opposed faculty governance and tenure at the law school level.

We cannot stand idly by and allow all that we have fought far be lost, whittled away, or destroyed. So I ask you to speak out and fight against the forces and people who would harm our field, our schools, our students, and future generations of lawyers. We may not win that fight. But fight it we must. So I ask you to join me in a second toast, using words from a Scotsman of the 17th Century.

I want to end with the words of James Graham, the First Marquis of Montrose.[6] He was deeply embroiled in the conflict between the Protestants and Catholics in 17th Century Scotland, in the fights between the Stuart Royalists and the Covenanter Republican forces. He became renowned for his military genius and is widely regarded as one of the greatest tacticians and strategists in European history, repeatedly winning battles against far superior forces. But he was widely renowned, too, for his integrity, for his dangerous and self-sacrificing stands, and for his poetry. We remember him now mostly for what has become known as “Montrose’s Toast,” a toast in which I would like you to join, as we continue to fight for the future of our field of legal writing:

He either fears his fate too much,

Or his desserts are small,

Who dares not put it to the touch,

To win or lose it all.[7]

Thank you.

-----------------

[1] Jack Achtenberg, Legal Writing and Research: The Neglected Orphan of the First Year, 29 U. Miami L. Rev. 218 (1975).

[2] Mary Ellen Gale, Legal Writing: The Impossible Takes a Little Longer, 44 Alb. L. Rev. 298, 320 (1980).

[3] Stephen G. Cary et al., Am. Friends Serv. Comm., Speak Truth to Power (1955), http://afsc.org/sites/afsc.civicactions.net/files/documents/Speak_Truth_to_Power.pdf.

[4] Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (2008).

[5] http://www.naomiklein.org/shock-doctrine.

[6] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Graham,_1st_Marquess_of_Montrose.

[7] See e.g. http://libertyhollow.weebly.com/1/post/2013/10/montroses-toast.html.